THE BIG LEAK

An Uneasy Evening with the Noir Legend

By Eddie Muller © 1999

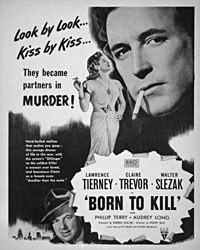

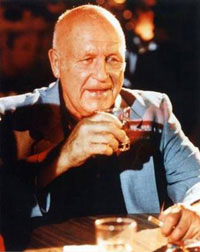

The meanest man in motion picture history sat beneath a palm tree, sucking wind. Twenty feet away, a line of ticket buyers snaked from the box office of the Egyptian Theater, down the frond-draped promenade, to Hollywood Boulevard. Patrons queuing for this revival of the noir classic Born to Kill barely noticed the hulking geezer who'd shuffled laboriously toward the theater entrance, then copped a squat to catch his breath. Most of them had come to see this movie, more than fifty years after its original release, because of the legend surrounding its leading man. They'd heard the tall tales of his cold-blooded persona, both on-screen and off.

Only a few of the hardcore noir junkies on line, murmuring to one another, surreptitiously pointing, recognized the relic in the crumpled fishing hat, wheezing under the palm, as the star they were shelling out seven-fifty to see. Nobody broke from the ranks to seek a handshake or an autograph. Even at 80, weakened by a stroke, Lawrence Tierney radiated an aura of menacing intimidation.

Dennis Bartok, programming director of the Egyptian, had scoped Tierney's approach from inside the lobby. Bartok heaved a deep sigh. Although Tierney lived nearby, he had not been invited to the screening. This was due, in full measure, to the actor's reputation as a loose cannon - a mockery of understatement.

Consider this assessment from no less an authority than Mickey Cohen, ruler of the Hollywood underworld when Tierney was in his hell-bent prime: "A lot of them actor guys—like the guy that played Dillinger, Lawrence Tierney—started to think they was Dillinger. I guess when actors are given a certain part to portray, and they portray it year in and year out, they begin to play it somewhat for real."

Robert Wise, director of Born to Kill, and the most genteelly mannered of filmmakers, was the evening's official guest of honor. But it was really Tierney, the living, breathing Noir Monster, that people were coming to see. I reminded Bartok of this, ignoring the dread that clouded his eyes. As co-programmer of the two-week noir series, I too was a guest of the American Cinematheque, which operated the Egyptian. I'd campaigned to show Born to Kill and was impressed Tierney had roused himself to attend. "Let's go get him," I nudged Dennis.

The actor responded to our greeting with a brusque command: "Pull my fucking arm!" Not the standard senior citizen's request for getting helped to their feet, but as I was about to learn, ordinary rules do not apply to Lawrence Tierney. Never have. Once we'd hoisted him upright, Tierney barked out an instruction manual for maneuvering him inside. "Get in close. Get a grip on my arms, both of you," he ordered, his voice like gargled gravel. "Take hold of my hand—tight, goddammit, tight!" Apparently this was how Tierney navigated daily life now-using people the way a drunk uses lampposts.

Despite his tottering gait, Tierney possessed prodigious strength in his upper body and a grip that could easily crack nuts. Yours, if you weren't careful. Throughout his tumultuous life, the actor blocked out his time equally among movie sets, saloons, and holding cells. In my book, Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir, I'd noted that Tierney had a rap sheet longer than his résumé:

In '48 he did three months for busting a guy's jaw in a ginmill. Same year he was charged with kicking a cop while drunk and disorderly—his seemingly perpetual state. In '52 he sparred with a professional welterweight on the corner of Broadway and 53rd. He was the only actor in Hollywood who stood for more mug shots than publicity photos: belted a cop in '56; simple assault in '57; kicked in a dame's door later that year; another jawbreaker in '58, as well as a dust-up with cops outside a 6th Avenue tavern. The day his mother killed herself in 1960, Tierney was arrested for breaking down a woman's door and assaulting her boyfriend. His torso still bears scars from an ill-advised tussle with a practiced knife-fighter.

Unpredictable, incorrigible, and belligerent—that's always been the book on Tierney.

Winded by the walk into the lobby, Tierney deposited himself in a folding chair. He had sufficient gas left, however, to muster a blatant come-on to Gwen Deglise, Bartok's comely and able assistant. Immediately tuning in on her Continental accent, Tierney displayed his unpredictability by using fluent French in an attempt to lure Gwen onto his lap. The man was incorrigible still.

He'd soon go three for three. I'd learn first-hand that Tierney is a human pitbull, conditioned and bred to strike at any perceived threat. I'd also find beneath the volatile veneer a complex, even sensitive, soul.

Once the nervous embarrassment about his debilitation subsided, Tierney's bluster mellowed into intriguing, discursive, palaver. Upon learning my name was Eddie, he lapsed into an Irish reverie about his late brother Ed, who'd followed Lawrence, and another thespian sibling, Girard (who renamed himself Scott Brady), from New York to Hollywood.

"Ed was a great guy, the best. I really loved that guy," Tierney sighed, his eyes growing distant. Could he have been recalling the time Ed came to a Santa Monica police station to go his bail, after Larry had been picked up, delirious on a church altar, pleading for sanctuary? Newspaper accounts of the incident had Larry popping brother Ed in the kisser as he was escorted to freedom.

Our conversation ran the gamut. One minute Larry extolled the glories of John Donne's poetry, the next he excoriated a one-time co-star with a febrile burst of invective. He was sharp, lucid and challenging—far from the demented gashound of legend. Whatever now fueled Tierney's outrageous fits of anti-social behavior, it wasn't demon rum. This night he was as sober as Sandra Day O'Connor.

Banter about our respective Celtic ancestors drifted into philosophical musings on the purpose, or pointlessness, of this mortal coil. Then, just as I was warming up to the man, literally letting my guard down, Tierney threw a short left hook toward my chin.

I jerked my head back, assumed a protective pose, and eyed my new pal suspiciously. "What the hell was that about?" I protested querulously.

"Don't gesture at me like that," he growled, still holding out the left like a threat. "People make fast moves around me, I react. I can't help it." Tierney favored me with the slit-eyed glower that had preceded many a barroom brawl. The moment passed. He slapped my knee and cracked a conspiratorial smile: "Help me to the head," Tierney said, reaching for my arm. "I gotta take a piss before the show."

I piloted Larry to the men's room, steered him to a urinal. Assisting in this project was a delicate young gentleman named Darrell, whom Tierney verbally abused throughout the arduous journey. We positioned Tierney before the porcelain, maintaining a discreet hold to stabilize his substantial bulk. An icebreaker was called for at this awkward moment. "I don't mind walking with you, Larry," I offered, "but if you think I'm gonna take it out and hold it for you, guess again." It was a calculated risk, trolling for some bawdy Irish badinage we might share.

Tierney broke off a guffaw. He wrapped a mitt around my neck and jerked me toward him. His bald dome banged my forehead. Despite the dull ache this headbutt inspired, I took it as a sign of affection. Real male bonding stuff.

As Tierney attended to his immediate priority, the restroom filled up with rubberneckers. Word had spread that Tierney, the mad dog himself, was in the head: not every day could you witness a micturating movie star. Soon, the cognoscenti had formed a semi-circle around the urinal. I signalled for them to grant some privacy. Legend or not, this was a guy struggling to cope with an eighty year-old bladder.

Not that Tierney needed my help. Zipping and pivoting, he squinted at the assembled gawkers. "What are you guys," he roared, "a bunch of fucking cocksuckers?" The throng tittered appreciatively. Better than a mere piss, they were getting USDA Prime Tierney.

He bulled through the gaggle of fans, Darrell and I still lending support. As we exited, who should enter but Robert Wise. Tierney loomed over him. Wise looked as if he was staring into the eyes of the Golem itself.

"Hello, Larry — how have you been?" the director chirped uneasily.

"Listen to me, Bob—" Tierney bellowed, reaching for the colorful cravat Wise sported. "I'm directing you now! Get the fuck over here!"

Wise, dodging deftly for an octogenarian, slipped Tierney's clutches and darted into the lavatory. "Good to see you Larry," he trailed off. Tierney muttered foul deprecations about various directors all the way to the doors of the auditorium.

Assessing the crowd, Tierney was gratified to see that at this late date, five decades after his headlining halcyon days, he could still pack a house. The steep aisle proved daunting to him, however. It occurred to me that the actor boomed bellicose to mask frustration at his deteriorating physical state. (As to what sparked his youthful bellicosity, I won't guess.) I offered to usher him down to a row reserved for special guests. "Ah, fuck it," he snarled in resignation. He didn't want the humiliation of appearing frail to an audience that had come to see a two-fisted, hell-raising he-man. We sat in the last row.

Bartok, swallowing his trepidation, announced that in addition to the evening's announced guest of honor, "We are also thrilled to have with us one of the stars of tonight's film, Mr. Lawrence Tierney." The ovation was accompanied by the kind of buzz usually associated with a bomb threat.

Tierney, however, proved to be a model moviegoer. Concerns that he might go off were unfounded. In fact, the first twenty or so minutes of the screening was an incredible kick. Tierney offered hushed asides about the making of the film, cited favorite lines of dialogue, and praised his co-stars: "Oh, here's Ester Howard. She steals the picture, she's the best thing in this movie," and "Me and Cookie [Elisha Cook, Jr.] used to go elk hunting together. We were good pals. Cookie was the greatest."

Soon Tierney whispered, with urgency: "Do me a favor, will ya? Go get me a cup."

"A cup of what?" I asked, confused. "Just a cup," Tierney implored, "An empty cup."

I returned a minute later with a jumbo-sized plastic Prince of Egypt soda cup. Without a moment's hesitation, Tierney stood up, dropped his trousers, and dispensed a jetstream into the capacious Dreamworks souvenir. I wished Spielberg-Katzenberg-Geffen could have been there. Never has a piece of shoddy, superfluous mass merchandising been put to such immediate and beneficial use. Of course, Tierney's relief did not go unnoticed. Even to uninitiated ears, the sound of a man pissing in a plastic cup isn't easily mistaken for anything else. Yet one woman in the row before us, for some unfathomable reason, required visual confirmation.

"What the fuck are you lookin' at" Tierney groused at the saucer-eyed spectator. "You never seen a cock before?" Sufficiently chastened, the woman redirected her gaze to the screen.

Once resituated, his own attention returned to the film, Tierney proved to be an expert on Born to Kill. He nudged me in anticipation of favorite dialogue, not just his own, but other actors', as well. He continued to regale me with sotto voce stories of his checkered cinema career: "I'll tell you who was a real genius—Val Lewton. He knew everything about making pictures," and "You know that picture I made, The Hoodlum, for Max Nosseck? I hate that picture. For some reason they always cast me as the mean asshole."

A disingenuous, but true, observation. In later years, Tierney still played mean assholes, for directors as disparate as Paul Morrisey (Andy Warhol's Bad), Norman Mailer (Tough Guys Don't Dance) and Quentin Tarantino (Reservoir Dogs).

At one point, with no prompting or provocation, Tierney latched onto my arm and seethed, like a line reading from one of his hard-boiled programmers: "I ain't afraid of nothing." Was some demon dogging him, prompting this spontaneous existential status report?

In between these incantations and recollections, Tierney topped off the cup three more times. Appalled sidelong glances from patrons were met with a gruff retort: "The movie's up there, you moronic cocksucker."

Granted that among 99.9 percent of the populace, makeshift urination in a crowded movie theater is viewed as an unseemly breach of social etiquette. Four public outpourings is beyond anyone's pale. But indulge a contrarian view. Lawrence Tierney is keenly aware of the narrow and nasty niche he occupies in movie history. He's proud of it. There won't be any honorary Oscars or lifetime achievement awards for this guy. A packed theater fifty years after the fact must suffice as his tribute. So excuse his incontinence while he soaks up the spectacle of 600 people watching his sinister chimera. What's the alternative? Hide in his apartment? Four exhausting hikes to the head? Soak himself in silence?

Or flesh out the legend a little bit more? Some choice. We should all be so brazen, maybe once or twice. Tierney's made a life out of it.

I note for the record that every bout with the cup, every tossed-off curse, was followed by a sincere, if significantly less voluble, request for absolution. "Please forgive me," Tierney would say, squeezing my leg for emphasis. "It's embarrassing, I know. I'm sorry." Every few minutes he'd nervously inquire about the Prince of Egypt's position, so fearful he was of it spilling. For what it's worth, his apologies seemed far more genuine than his foul-mouthed bombast.

The evening concluded with no fatalities. Although I feared Bob Wise might keel over when Tierney, miffed at what he perceived as several self-serving comments during the director's post-screening interview, hollered mightily from his back row perch: "Hey Bob, who wrote the fucking script?"

This brought from the crowd calls of "Let Larry talk!" as well as some anxious verbal tapdancing from Wise. Tierney waved off the clamor, settling back in his seat and muttering, "The whole goddamn picture was right there in the script. The writers never get any fucking credit."

At the close of the show, a mob swarmed Tierney before he could leave his seat. Being hemmed-in does not suit the man. "Get the hell away from me or I'll kill all you motherfuckers," he snarled. At this stage of Tierney's life, in which he's less likely to follow through, such a declaration merely draws more moths to the flame. Fans flit around him, eager for the expected eruption. Greetings are offered at greater than arm's length. Photos are covertly snapped from a safe distance. Tierney is treated like a wild animal, one tranquilized and taken captive by time's inexorable erosion.

One of these days the Noir Monster will eventually succumb to the inevitable. If the power in charge is merciful, Tierney will be let off the hook in his sleep. If the power is just, we'll read about Tierney being carted off from some fatal streetcorner fracas. Either way, the gawkers should get together and muster a collection for an appropriately inscribed headstone. Let the chiseling begin: He Did Not Go Quietly.

© All right reserved. Reproduction of this article without the express written permission of the author, or the MWA, is strictly prohibited.