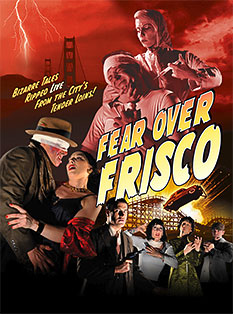

Thrillpeddlers presents Shocktoberfest 12

FEAR OVER FRISCO

The 12th Annual Extravaganza of Terror and Titillation

A Trio of "Noir-Horror" Stage Plays by "Czar of Noir" Eddie Muller

Sept. 23 – Nov. 19, 2011 (Thurs., Fri. & Sat. at 8:00 pm)

at The Hypnodrome Theatre, 575 10th St., San Francisco, CA

The sanguinary spectacle of the Grand Guignol seeps into the shadowy cinematic world of film noir in "Shocktoberfest!! 12: FEAR OVER FRISCO," a collaboration between the city's renowned Thrillpeddlers and "Czar of Noir" Eddie Muller, author of the evening's three plays. Each tale leads the audience through a different period of San Francisco's noir-stained history: the contemporary déjà vu dread of "The Grand Inquisitor," the post-WWII hysterics of "An Obvious Explanation," and the Prohibition era high- and low-life of "The Drug." In addition, the show features musical director Scrumbly Koldewyn's merrily macabre musical interludes, including a theme song penned by Koldewyn and Muller.

"There's an obvious affinity between the Theatre du Grand Guignol and film noir," says Eddie Muller. "It's in the depiction of desperate characters acting on their worst instincts. It seems natural —inevitable, even—that the Thrillpeddlers and I would create an unholy union of the two, in a city that's been so supportive of both genres."

In THE GRAND INQUISITOR, an odd young woman with a cache of used books comes calling on an elderly recluse that she believes is the widow of San Francisco's most notorious serial killer. Twenty real-time minutes culminate in an unexpected and shocking climax.

Cast: Mary Gibboney (Hazel), Bonni Suval (Lulu)

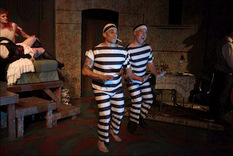

A daring heist goes awry in AN OBVIOUS EXPLANATION when the crook who stashed the loot suffers amnesia. An ambitious doctor intends to solve the problem with her untested "memory" serum. The results are more dramatic than she expected—which is not a good thing.

Cast: Flynn De Marco (Frank), Daniel Bakken (Lucky), Bonni Suval (Dr. Lorrison), Zelda Koznofski (Sherry), Eric Tyson Wertz (Police Captain)

In THE DRUG, a promising young deputy DA's efforts to crack the case of a celebrated artist's disfigurement are thwarted—by the prosecutor's own desire for the prime suspect. René Berton's classic two-act Grand Guignol, originally set in Saigon, is transposed and adapted by Muller to 1929 San Francisco.

Cast: Eric Tyson Wertz (Brendan McDonagh), Flynn De Marco (Charles Marzac), Kära Emry (Claudine), Daniel Bakken (Van Ness), Joshua Devore (Bernard), Jim Jeske (The Captain), Russell Blackwood (The Doctor), Steve Bolinger (The Editor), Birdie-Bob Watt (Luang-Si), Ste Fishell (Robert)

NOIR GUIGNOL

Eddie Muller talks about creating his hybrid horror-noir stage show, Fear Over Frisco

Interview by Anne Hockens

How did you come to collaborate with the Thrillpeddlers?

Russell Blackwood, the Thrillpeddlers' artistic director came to a book signing of mine many years ago. He'd read Grindhouse, my history of sexploitation films, and wanted me to act as a dramaturg for a production he was doing of the play Woman Behind Bars. He wanted me to explain to the cast how to deal with "camp" material in its original context—to make them understand the original theatricality of the films the play was based on; he believed this would take the "winking" out of the performances, and make it more truthful without sacrificing the humor. I guess it worked, because he invited me to become part of the Thrillpeddlers "family" after that. I was with him when he first entered the space that would become the Hypnodrome (the troupe's home theater in San Francisco). His goal was to recreate Paris's original Grand Guignol experience for a contemporary audience. I worked on the first three productions at the Hypnodrome.

Why do you think Grand Guignol still draws an audience today?

Well, I don't know that it does. I mean, this is a small theatre and it isn't easy to fill. To me, Grand Guignol's influence is pervasive today, but not many people know about the original theater in Paris, or how controversial and influential it was. To me, Grand Guignol's strategy was to find society's hot buttons and push them in the most devilishly entertaining way. And it daringly did this by combining humor and horror, which makes perfect sense to me. Frankly, traditional Grand Guignol is a hard sell in the Saw and Hostel era. You might argue that films such as those extend the tradition, but I can't convince myself of it. I don't believe Grand Guignol desensitized people to violence and horror—it actually made them face it and react to it. Horror today is pervasive and easy. It's like a drug; viewers grow immune and just look for bigger shocks, ignoring the context.

In what ways do Grand Guignol and film noir overlap?

Both are about characters stepping over the line into darkness and reaping the consequences of bad decisions. That's true of every pure noir, and every Grand Guignol play. In noir, the instruments of doom are commonplace: lust and money, mostly. In Grand Guignol, the scenarios stretch into the realm of the fantastic: life after death, mad sciences, hypnotism, etc. But you know the drill: somebody does something they know is wrong … and then there's hell to pay.

The evening starts with the musical number "Fear Over Frisco" for which you wrote the lyrics. Was this your first foray into song writing? What did you hope to accomplish with the piece in terms of the evening's entertainment?

I was so excited to create a song! It allowed me to imagine I was Cole Porter or Lorenz Hart for a couple of days. I admire old school lyricists who could write complicated, sophisticated lines and make them dance. Well, it was Scrumbly Kodelwyn (legendary Cockettes composer) who made it work. I'd originally conceived the song as the sort of thing Tom Waits might do, a bluesy swing for piano and bass. But then more and more cast members wanted to be in it, and it became a traditional "call and response" show tune. We wanted an overture, something to grab the audience and set the tone. It's a throwback to old Hollywood: yeah, this is a melodrama, but we're gonna stop for a few minutes to give you a musical number. There're three of them: "Fear Over Frisco," Johnny Mercer's "I Remember You," and Irving Berlin's "Pack Up Your Sins and Go to the Devil." Lots of entertainment value for the price.

How do the individual pieces in the night's entertainment form an overall view of San Francisco?

They don't, really. I just wanted to have fun showcasing the city's dark history. And find the differences and similarities between noir stories set in 1929, 1948, and 2000. In terms of both crime and horror, and they way those types of stories are enacted within their original timeframe. Throw in the song, and this was my attempt to create a noir ode to the city, my hometown.

This is the third format in which you've told the tale of The Grand Inquisitor. In what ways does the format (short story, film, live theater) inform the story? Also, why do you think you keep coming back to this piece?

I keep coming back to it because it might be the most significant thing I've written. Most serial killer stories are bullshit, plain and simple. This piece is unusual in that it's about things that are never in such stories: sadness, regret, guilt, forgiveness. And it's about women and how they are caught up in male madness. All that's in there, yet in all the crucial ways, it's still Grand Guignol theater. It's a flat-out life-and-death story told in 20 minutes. And while I loved making the film version with Marsha Hunt, and I'm very proud of it, I was compelled to put this before a live audience minus any cinematic tricks—no cutaways, no close-ups, etc. It's all about the actors, and how they inhabit these two characters. I was lucky to get two terrific actresses, Mary Gibboney (Hazel) and Bonni Suval (Lulu). The performance last night was very moving—I realized that the piece was no longer mine; they'd taken it over and made it their own. I was watching them and wondering, "How is this going to turn out?" That's the gift really good actors give a writer. It's like in The Exorcist when Father Karras sacrifices himself to absorb the demon—"Come into me!" Bonni and Mary liberated me, by making these characters their own. It's a rare gift.

What inspired you to write An Obvious Explanation? I find it to be both homage to and a parody of noir. How does the satire in the piece illuminate your feelings towards, and insights into, noir?

I simply wanted it to be fun … but in a wicked way. It's seems light and breezy, but it keeps careening toward mayhem. That's what I love about the good B noirs; at the same time they were goofy and easy to dismiss, they created a very twitchy, uncomfortable sense of dread. If anything, the piece is an homage to the way those films make me feel—sort of giddily delighted but guilty for loving them so much. As a practical matter of stagecraft, I wanted to face the challenge of translating to the stage all the stuff I love about noir cinema—the lighting, the melodramatic revelations, the convoluted plotting, the face-slapping. Flynn DeMarco, who plays Frank, totally got it, right from the start. He didn't even have to audition. He simply said "I'd play this guy like Dan Duryea in Scarlet Street," and the part was his. Audiences seem to have a ball with this play, even if they don't get all the noir references. Also, the pace is a tribute to the old films—the damn thing hits its stride and is over before you know it. We don't overstay our welcome.

How does having a lighter piece in between the two darker ones (a format Le Théâtre du Grand Guignol also employed) affect the impact of the pieces on the audience?

Well, that's in keeping with Grand Guignol tradition. They called them "hot and cold showers." The audience is never sure when a play starts whether it's going to terrify them or make them laugh. And that's risky … sometimes people start chuckling in the first few minutes of Inquisitor and I live for the moment when the theater falls completely silent and people are holding their breath. I heard a woman the other night spontaneously shout "Oh my God, no!" at the end. Who could ask for more? Explanation works the opposite way: It's a contraption that starts coming apart. It seems sort of serious at the start and just goes downhill, without brakes, toward a crash-and-burn finish. The cast doesn't have to worry about anything but big emotions and pace. Go fast, go hard.

I was impressed that Bonni Suval changed characters so fast from Lulu in The Grand Inquisitor to her very different role in An Obvious Explanation. Not just in terms of character but in tone, too! I found it funny that in Explanation she was named Dr. Ann Lorrison (Audrey Totter's character from High Wall [1947]), although this Dr. Lorrison was not so compassionate.

Isn't she great? Well, Bonni made more of Dr. Lorrison than was actually written. She brought a wily, wicked streak to the character that wasn't on the page. It was fun to see it grow organically. She gave a really good reading, so it started with how adept she was with the dialogue. Then over the course of rehearsal we kept building her look—the coat, scarf, platinum hair—until on opening night we finally found the perfect shoes and she sashayed out on those five-inch heels. When Bonni goes hard and fast, like Stanwyck, she's got the audience right in her hands.

How faithful is The Drug to the original play? What did you change and why?

It's faithful in structure, perhaps a little too much so. Rene Berton's original play, written in 1927, was set in French Colonial Saigon and contains details incomprehensible to a contemporary audience. But we wanted to feature, in Thrillpeddlers' "Shocktoberfest" tradition, one adaptation of a classic Grand Guignol play. So I transposed the setting to Prohibition-era San Francisco right before the stock market crash. The big "shock" of the original was the trip inside the opium den, which allowed the French bourgeoisie a glimpse into the underworld. No big deal today, so the piece can't help but play as a curio. Most of my changes had to do with character things, trying to create multiple levels to their motivations. In essence, making it less a horror piece and more a noir piece.

One of the interesting aspects of this show is that all three stories ultimately center on women; the first piece is a two-woman play, and women drive the action in the other two. In each, the women deal with different aspects of patriarchal oppression: a violent husband; sexism in professional life; and men's inability to understand female sexuality (and their desire to exploit or repress it). Was this deliberate on your part when you put the pieces together? Or does the crime/horror genre inherently deal with conflict between the sexes? Or both?

I like to write female characters. That's the simplest answer. But I think your observation is valid. I was conscious of those things when writing and directing The Grand Inquisitor and Obvious Explanation. Lulu and Dr. Lorrison are sisters in a way—as women they won't get credit for solving a big mystery, and they know it. That's what drives them to take desperate action. These types of women always show up in my stories—smart, highly sexualized, and struggling against male stereotyping. This is something that's clearly there in classic film noir, but I like to push it a little further while maintaining the style and allure of the classic era. If I'd had my way with Berton's Drug, I probably would have totally overhauled the character of Claudine, the femme fatale. She's too passive for my taste. The other recurring theme of the show is drug use. In each play the plot turns on a character's reaction to a drug they're given. This was really common in classic Grand Guignol theatre, and it's still a useful shorthand for exploring people's desire for, and dread of, the loss of control.